- Reflectarray With Variable Slots On Ground Plane Video

- Reflectarray With Variable Slots On Ground Plane Crash

- Reflectarray With Variable Slots On Ground Planes

- Reflectarray With Variable Slots On Ground Planet

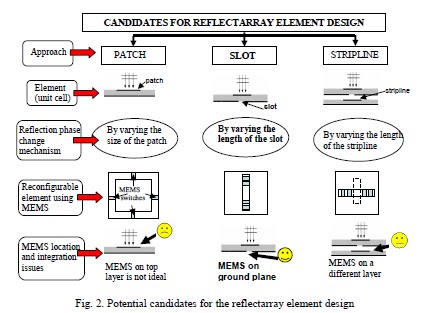

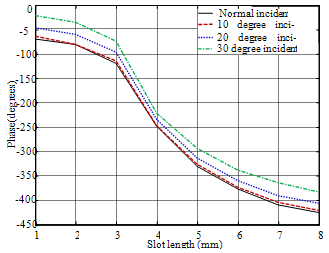

Various reflectarray element designs were considered which included variable size patches, patch with variable length slot, patch with fixed slot fed by variable length stripline. After careful study and systematic evaluation, it was decided that the element – patch with variable length slot in the ground plane was best suited. A circularly polarised millimetre-wave reflectarray antenna based on cross-slots of varying length couple through a patch as the cell element is introduced. Far-field radiation pattern, gain and axial ratio are presented and compared with a reflectarray that employs cross-dipoles as its cell element. Ka-band variable DRA reflectarray lengths supported on substrate of same dielectric constant of DRA was de-signed14. A X-band rectangular DRA and circular polari-zation at X-band15 are investigated. Dual DRA sizes supported on ground plane with variable slot lengths is il-lustrated in16 for getting full phase cycle using superposi-tion.

In telecommunications and radar, a reflective array antenna is a class of directiveantennas in which multiple driven elements are mounted in front of a flat surface designed to reflect the radio waves in a desired direction. They are a type of array antenna. They are often used in the VHF and UHF frequency bands. VHF examples are generally large and resemble a highway billboard, so they are sometimes called billboard antennas, or in Britain hoarding antennas. Other names are bedspring array[1] and bowtie array depending on the type of elements making up the antenna. The curtain array is a larger version used by shortwave radio broadcasting stations.

Reflective array antennas usually have a number of identical driven elements, fed in phase, in front of a flat, electrically large reflecting surface to produce a unidirectional beam of radio waves, increasing antenna gain and reducing radiation in unwanted directions. The larger the number of elements used, the higher the gain; the narrower the beam is and the smaller the sidelobes are. The individual elements are most commonly half wave dipoles, although they sometimes contain parasitic elements as well as driven elements. The reflector may be a metal sheet or more commonly a wire screen. A metal screen reflects radio waves as well as a solid metal sheet as long as the holes in the screen are smaller than about one-tenth of a wavelength, so screens are often used to reduce weight and wind loads on the antenna. They usually consist of a grill of parallel wires or rods, oriented parallel to the axis of the dipole elements.

The driven elements are fed by a network of transmission lines, which divide the power from the RF source equally between the elements. This often has the circuit geometry of a tree structure.

- 1Basic concepts

Basic concepts[edit]

Radio signals[edit]

When a radio signal passes a conductor, it induces an electrical current in it. Since the radio signal fills space, and the conductor has a finite size, the induced currents add up or cancel out as they move along the conductor. A basic goal of antenna design is to make the currents add up to a maximum at the point where the energy is tapped off. To do this, the antenna elements are sized in relation to the wavelength of the radio signal, with the aim of setting up standing waves of current that are maximized at the feed point.

This means that an antenna designed to receive a particular wavelength has a natural size. To improve reception, one cannot simply make the antenna larger; this will improve the amount of signal intercepted by the antenna, which is largely a function of area, but will lower the efficiency of the reception (at a given wavelength). Thus, in order to improve reception, antenna designers often use multiple elements, combining them together so their signals add up. These are known as antenna arrays.

Array phasing[edit]

In order for the signals to add together, they need to arrive in-phase. Consider two dipole antennas placed in a line end-to-end, or collinear. If the resulting array is pointed directly at the source signal, both dipoles will see the same instantaneous signal, and thus their reception will be in-phase. However, if one were to rotate the antenna so it was at an angle to the signal, the extra path from the signal to the more distant dipole means it receives the signal slightly out of phase. When the two signals are then added up, they no longer strictly reinforce each other, and the output drops. This makes the array more sensitive horizontally, while stacking the dipoles in parallel narrows the pattern vertically. This allows the designer to tailor the reception pattern, and thus the gain, by moving the elements about.

If the antenna is properly aligned with the signal, at any given instant in time, all of the elements in an array will receive the same signal and be in-phase. However, the output from each element has to be gathered up at a single feed point, and as the signals travel across the antenna to that point, their phase is changing. In a two-element array this is not a problem because the feed point can be placed between them; any phase shift taking place in the transmission lines is equal for both elements. However, if one extends this to a four-element array, this approach no longer works, as the signal from the outer pair has to travel further and will thus be at a different phase than the inner pair when it reaches the center. To ensure that they all arrive with the same phase, it is common to see additional transmission wire inserted in the signal path, or for the transmission line to be crossed over to reverse the phase if the difference is greater than 1⁄2 a wavelength.

Reflectarray With Variable Slots On Ground Plane Video

Reflectors[edit]

The gain can be further improved through the addition of a reflector. Generally any conductor in a flat sheet will act in a mirror-like fashion for radio signals, but this also holds true for non-continuous surfaces as long as the gaps between the conductors are less than about 1⁄10 of the target wavelength.[2] This means that wire mesh or even parallel wires or metal bars can be used, which is especially useful both for reducing the total amount of material as well as reducing wind loads.

Due to the change in signal propagation direction on reflection, the signal undergoes a reversal of phase. In order for the reflector to add to the output signal, it has to reach the elements in-phase. Generally this would require the reflector to be placed at 1⁄2 of a wavelength behind the elements, and this can be seen in many common reflector arrays like television antennas. However, there are a number of factors that can change this distance, and actual reflector positioning varies.

Reflectors also have the advantage of reducing the signal received from the back of the antenna. Signals received from the rear and re-broadcast from the reflector have not undergone a change of phase, and do not add to the signal from the front. This greatly improves the front-to-back ratio of the antenna, making it more directional. This can be useful when a more directional signal is desired, or unwanted signals are present. There are cases when this is not desirable, and although reflectors are commonly seen in array antennas, they are not universal. For instance, while UHF television antennas often use an array of bowtie antennas with a reflector, a bowtie array without a reflector is a relatively common design in the microwave region.[3]

Gain limits[edit]

As more elements are added to an array, the beamwidth of the antenna's main lobe decreases, leading to an increase in gain. In theory there is no limit to this process. However, as the number of elements increases, the complexity of the required feed network that keeps the signals in-phase increases. Ultimately, the rising inherent losses in the feed network become greater than the additional gain achieved with more elements, limiting the maximum gain that can be achieved.

Reflectarray With Variable Slots On Ground Plane Crash

The gain of practical array antennas is limited to about 25 - 30 dB. Two half wave elements spaced a half wave apart and a quarter wave from a reflecting screen have been used as a standard gain antenna with about 9.8 dBi at its design frequency.[4] Common 4-bay television antennas have gains around 10 to 12 dB,[5] and 8-bay designs might increase this to 12 to 16 dB.[6] The 32-element SCR-270 had a gain around 19.8 dB.[7] Some very large reflective arrays have been constructed, notably the Soviet Duga radars which are hundreds of meters across and contain hundreds of elements. Active array antennas, in which groups of elements are driven by separate RF amplifiers, can have much higher gain, but are prohibitively expensive.

Since the 1980s, versions for use at microwave frequencies have been made with patch antenna elements mounted in front of a metal surface.[8]

Radiation pattern and beam steering[edit]

When driven in phase, the radiation pattern of the reflective array is a single main lobe perpendicular to the plane of the antenna, plus several sidelobes at equal angles to either side. The more elements used, the narrower the main lobe and the less power is radiated in the sidelobes.

The main lobe of the antenna can be steered electronically within a limited angle by phase shifting the drive signals applied to the individual elements. Each antenna element is fed through a phase shifter which can be controlled digitally, delaying each signal by a successive amount. This causes the wavefronts created by the superposition of the individual elements to be at an angle to the plane of the antenna. Antennas that use this technique are called phased arrays and often used in modern radar systems.

Another option for steering the beam is mounting the entire antenna structure on a pivoting platform and rotating it mechanically.

See also[edit]

- Mars Cube One (2018 spacecraft design with Reflective array antenna)

References[edit]

- ^US Navy (September 1998). NAVEDTRA 14183 - Navy Electricity and Electronics Training Series. Module 11 - Microwave principles. Lulu Press. p. 236. ISBN1329667700.

- ^'The Effects of Earth's Upper Atmosphere on Radio Signals'. NASA.

- ^Raut, S. (July 2014). 'Wideband printed bowtie array for spectrum monitoring'. 2014 IEEE Antennas and Propagation Society International Symposium (APSURSI). Antennas and Propagation Society International Symposium. pp. 235–236. doi:10.1109/APS.2014.6904449. ISBN978-1-4799-3540-6.

- ^'Standard Gain Antennas'.

- ^'ULTRAtenna 60'. Channel Master.

- ^'EXTREMEtenna 80'. Channel Master.

- ^Burrows, Chas. R. (2013-10-22). Radio Wave Propagation. p. 460. ISBN9781483258546.

- ^Huang, john. Reflectarray antennas.

This article incorporates public domain material from the General Services Administration document 'Federal Standard 1037C' (in support of MIL-STD-188).

In telecommunications and radar, a reflective array antenna is a class of directiveantennas in which multiple driven elements are mounted in front of a flat surface designed to reflect the radio waves in a desired direction. They are a type of array antenna. They are often used in the VHF and UHF frequency bands. VHF examples are generally large and resemble a highway billboard, so they are sometimes called billboard antennas, or in Britain hoarding antennas. Other names are bedspring array[1] and bowtie array depending on the type of elements making up the antenna. The curtain array is a larger version used by shortwave radio broadcasting stations.

Reflective array antennas usually have a number of identical driven elements, fed in phase, in front of a flat, electrically large reflecting surface to produce a unidirectional beam of radio waves, increasing antenna gain and reducing radiation in unwanted directions. The larger the number of elements used, the higher the gain; the narrower the beam is and the smaller the sidelobes are. The individual elements are most commonly half wave dipoles, although they sometimes contain parasitic elements as well as driven elements. The reflector may be a metal sheet or more commonly a wire screen. A metal screen reflects radio waves as well as a solid metal sheet as long as the holes in the screen are smaller than about one-tenth of a wavelength, so screens are often used to reduce weight and wind loads on the antenna. They usually consist of a grill of parallel wires or rods, oriented parallel to the axis of the dipole elements.

The driven elements are fed by a network of transmission lines, which divide the power from the RF source equally between the elements. This often has the circuit geometry of a tree structure.

- 1Basic concepts

Basic concepts[edit]

Radio signals[edit]

When a radio signal passes a conductor, it induces an electrical current in it. Since the radio signal fills space, and the conductor has a finite size, the induced currents add up or cancel out as they move along the conductor. A basic goal of antenna design is to make the currents add up to a maximum at the point where the energy is tapped off. To do this, the antenna elements are sized in relation to the wavelength of the radio signal, with the aim of setting up standing waves of current that are maximized at the feed point.

This means that an antenna designed to receive a particular wavelength has a natural size. To improve reception, one cannot simply make the antenna larger; this will improve the amount of signal intercepted by the antenna, which is largely a function of area, but will lower the efficiency of the reception (at a given wavelength). Thus, in order to improve reception, antenna designers often use multiple elements, combining them together so their signals add up. These are known as antenna arrays.

Array phasing[edit]

In order for the signals to add together, they need to arrive in-phase. Consider two dipole antennas placed in a line end-to-end, or collinear. If the resulting array is pointed directly at the source signal, both dipoles will see the same instantaneous signal, and thus their reception will be in-phase. However, if one were to rotate the antenna so it was at an angle to the signal, the extra path from the signal to the more distant dipole means it receives the signal slightly out of phase. When the two signals are then added up, they no longer strictly reinforce each other, and the output drops. This makes the array more sensitive horizontally, while stacking the dipoles in parallel narrows the pattern vertically. This allows the designer to tailor the reception pattern, and thus the gain, by moving the elements about.

If the antenna is properly aligned with the signal, at any given instant in time, all of the elements in an array will receive the same signal and be in-phase. However, the output from each element has to be gathered up at a single feed point, and as the signals travel across the antenna to that point, their phase is changing. In a two-element array this is not a problem because the feed point can be placed between them; any phase shift taking place in the transmission lines is equal for both elements. However, if one extends this to a four-element array, this approach no longer works, as the signal from the outer pair has to travel further and will thus be at a different phase than the inner pair when it reaches the center. To ensure that they all arrive with the same phase, it is common to see additional transmission wire inserted in the signal path, or for the transmission line to be crossed over to reverse the phase if the difference is greater than 1⁄2 a wavelength.

Reflectors[edit]

The gain can be further improved through the addition of a reflector. Generally any conductor in a flat sheet will act in a mirror-like fashion for radio signals, but this also holds true for non-continuous surfaces as long as the gaps between the conductors are less than about 1⁄10 of the target wavelength.[2] This means that wire mesh or even parallel wires or metal bars can be used, which is especially useful both for reducing the total amount of material as well as reducing wind loads.

Due to the change in signal propagation direction on reflection, the signal undergoes a reversal of phase. In order for the reflector to add to the output signal, it has to reach the elements in-phase. Generally this would require the reflector to be placed at 1⁄2 of a wavelength behind the elements, and this can be seen in many common reflector arrays like television antennas. However, there are a number of factors that can change this distance, and actual reflector positioning varies.

Reflectors also have the advantage of reducing the signal received from the back of the antenna. Signals received from the rear and re-broadcast from the reflector have not undergone a change of phase, and do not add to the signal from the front. This greatly improves the front-to-back ratio of the antenna, making it more directional. This can be useful when a more directional signal is desired, or unwanted signals are present. There are cases when this is not desirable, and although reflectors are commonly seen in array antennas, they are not universal. For instance, while UHF television antennas often use an array of bowtie antennas with a reflector, a bowtie array without a reflector is a relatively common design in the microwave region.[3]

Gain limits[edit]

As more elements are added to an array, the beamwidth of the antenna's main lobe decreases, leading to an increase in gain. In theory there is no limit to this process. However, as the number of elements increases, the complexity of the required feed network that keeps the signals in-phase increases. Ultimately, the rising inherent losses in the feed network become greater than the additional gain achieved with more elements, limiting the maximum gain that can be achieved.

The gain of practical array antennas is limited to about 25 - 30 dB. Two half wave elements spaced a half wave apart and a quarter wave from a reflecting screen have been used as a standard gain antenna with about 9.8 dBi at its design frequency.[4] Common 4-bay television antennas have gains around 10 to 12 dB,[5] and 8-bay designs might increase this to 12 to 16 dB.[6] The 32-element SCR-270 had a gain around 19.8 dB.[7] Some very large reflective arrays have been constructed, notably the Soviet Duga radars which are hundreds of meters across and contain hundreds of elements. Active array antennas, in which groups of elements are driven by separate RF amplifiers, can have much higher gain, but are prohibitively expensive.

Since the 1980s, versions for use at microwave frequencies have been made with patch antenna elements mounted in front of a metal surface.[8]

Radiation pattern and beam steering[edit]

When driven in phase, the radiation pattern of the reflective array is a single main lobe perpendicular to the plane of the antenna, plus several sidelobes at equal angles to either side. The more elements used, the narrower the main lobe and the less power is radiated in the sidelobes.

The main lobe of the antenna can be steered electronically within a limited angle by phase shifting the drive signals applied to the individual elements. Each antenna element is fed through a phase shifter which can be controlled digitally, delaying each signal by a successive amount. This causes the wavefronts created by the superposition of the individual elements to be at an angle to the plane of the antenna. Antennas that use this technique are called phased arrays and often used in modern radar systems.

Another option for steering the beam is mounting the entire antenna structure on a pivoting platform and rotating it mechanically.

See also[edit]

- Mars Cube One (2018 spacecraft design with Reflective array antenna)

References[edit]

- ^US Navy (September 1998). NAVEDTRA 14183 - Navy Electricity and Electronics Training Series. Module 11 - Microwave principles. Lulu Press. p. 236. ISBN1329667700.

- ^'The Effects of Earth's Upper Atmosphere on Radio Signals'. NASA.

- ^Raut, S. (July 2014). 'Wideband printed bowtie array for spectrum monitoring'. 2014 IEEE Antennas and Propagation Society International Symposium (APSURSI). Antennas and Propagation Society International Symposium. pp. 235–236. doi:10.1109/APS.2014.6904449. ISBN978-1-4799-3540-6.

- ^'Standard Gain Antennas'.

- ^'ULTRAtenna 60'. Channel Master.

- ^'EXTREMEtenna 80'. Channel Master.

- ^Burrows, Chas. R. (2013-10-22). Radio Wave Propagation. p. 460. ISBN9781483258546.

- ^Huang, john. Reflectarray antennas.

This article incorporates public domain material from the General Services Administration document 'Federal Standard 1037C' (in support of MIL-STD-188).